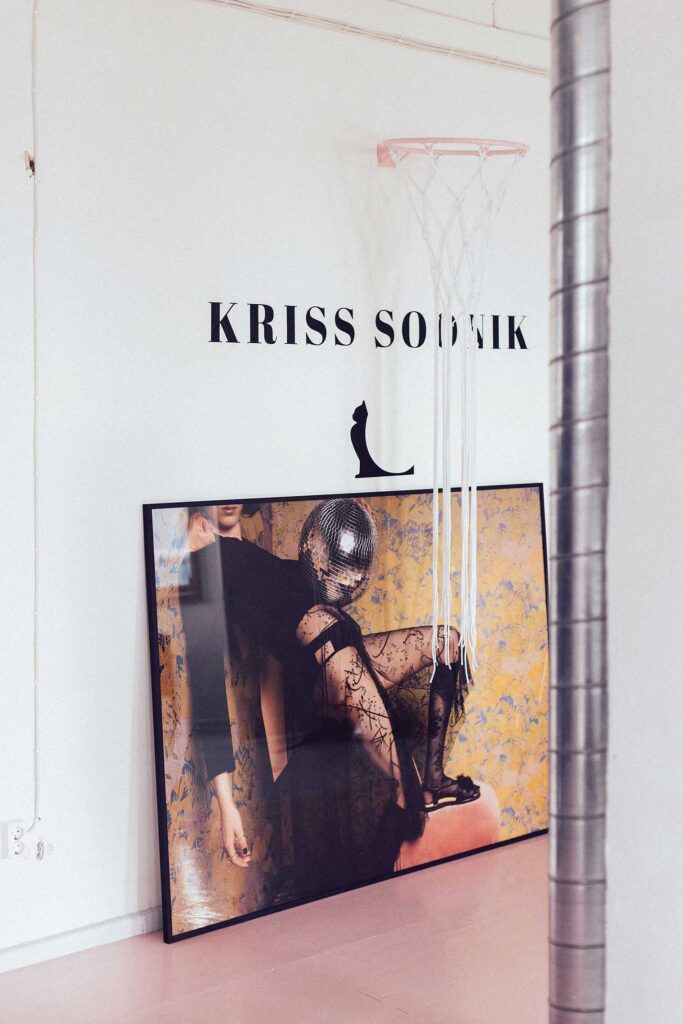

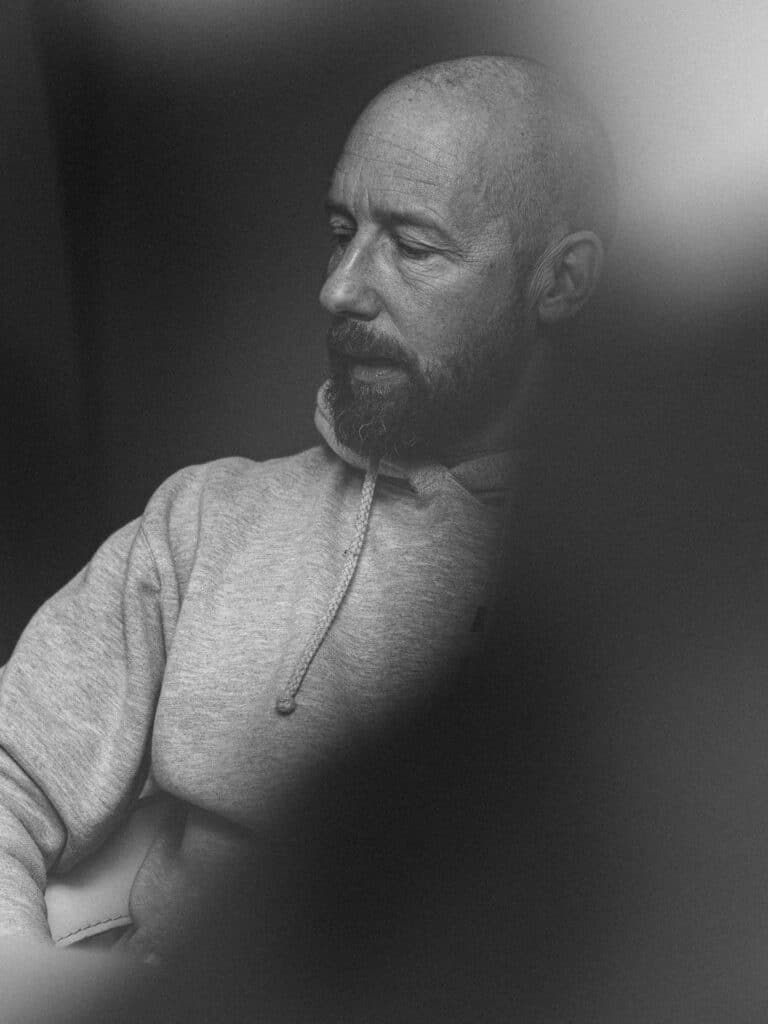

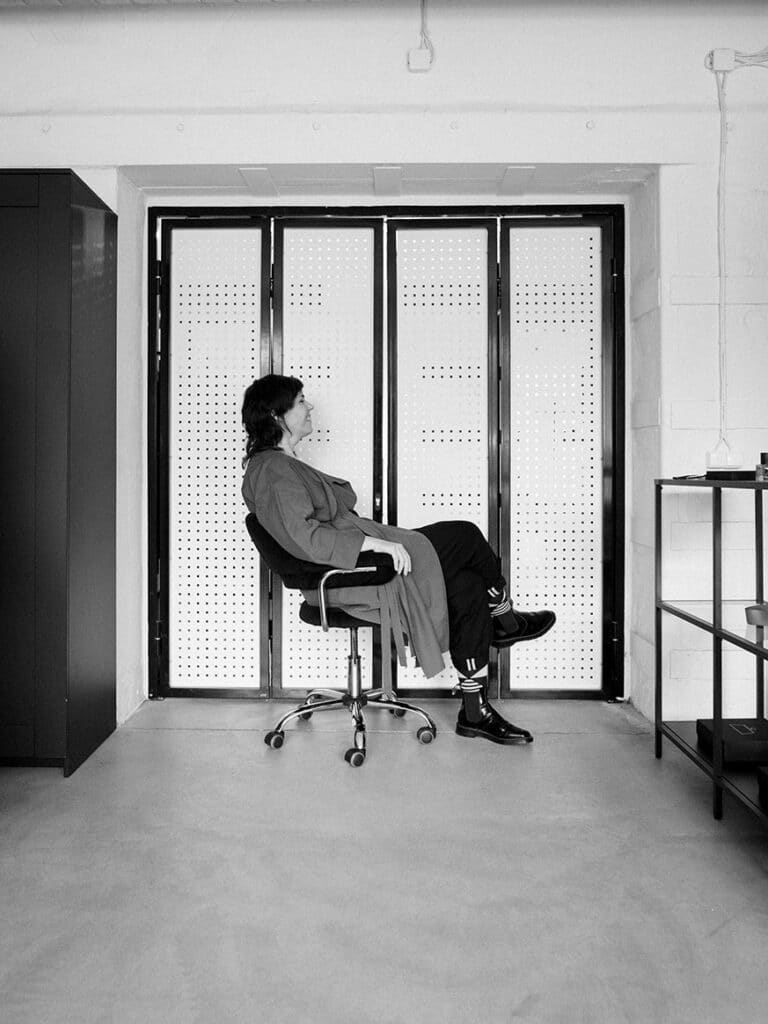

On a crisp winter morning, our Artist Series project visited the newly opened New Life Studio atelier on Toompea. The brand’s creators, Eva Lotta Tarn and Tuuliki Peil, come from completely different backgrounds, yet they are united by a similar mindset and a shared desire to create ethical design.

Eva Lotta is a graduate of the Estonian Academy of Arts, specializing in accessory design. Tuuliki has an educational background in philosophy, theology, and psychotherapy, and is self-taught in design.

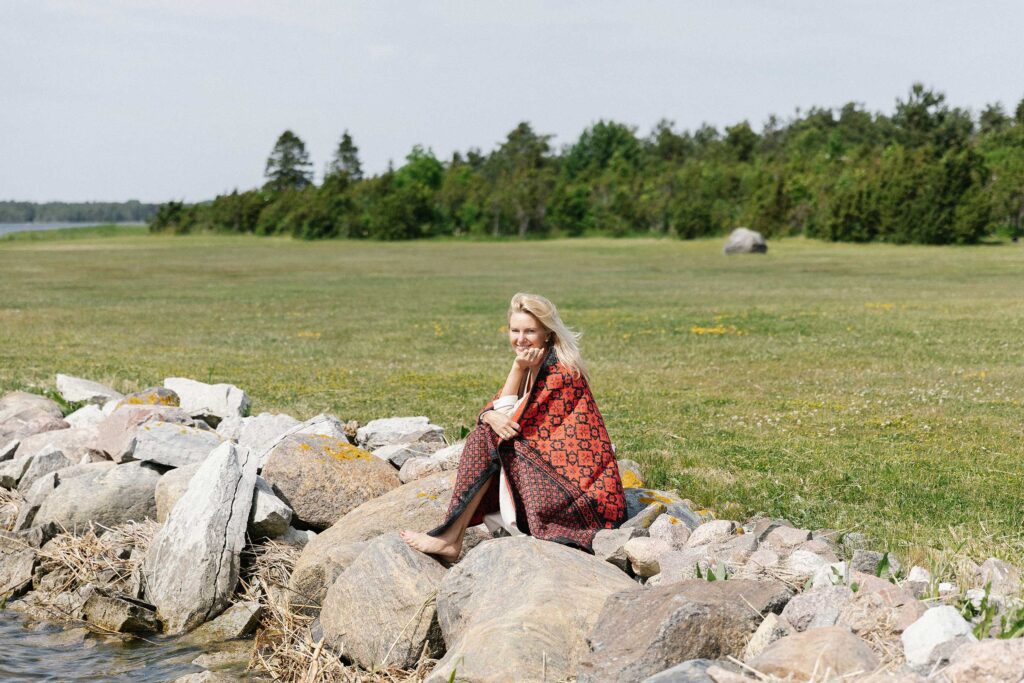

Eva Lotta says that her relationship with design exists on “a razor-thin line between love and hate.” “If I could choose absolutely any other field, I would do something else. This is not an easy profession, and I haven’t made my life any easier by choosing it,” she admits. Yet she always finds her way back to creation. “I need to express myself through making things, and it’s important to me that what I create has practical value. I didn’t choose this – it chose me, and I don’t know how to exist without it.”

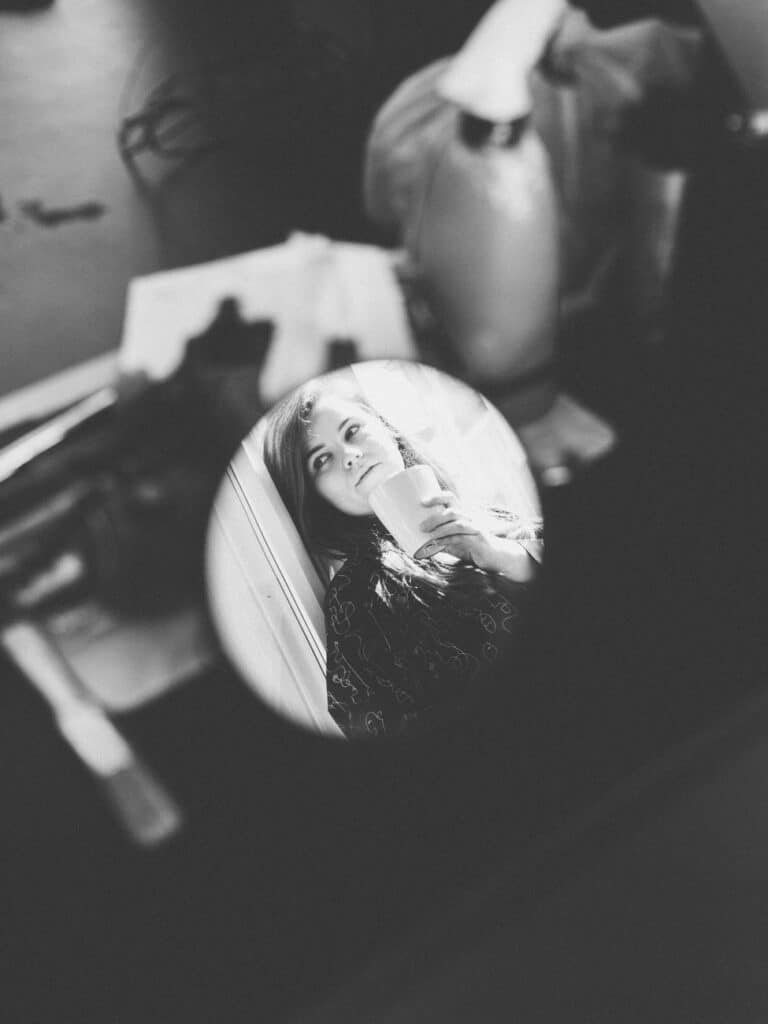

Tuuliki fully agrees. “One hundred percent the same story. I’ve tried many times in my life to step out of the role of a designer and do the things I’ve studied. But it doesn’t work – it just doesn’t work at all. I’m constantly registering things, for example in nature: colour combinations, textures, moments, and thinking about what I could do with them.”

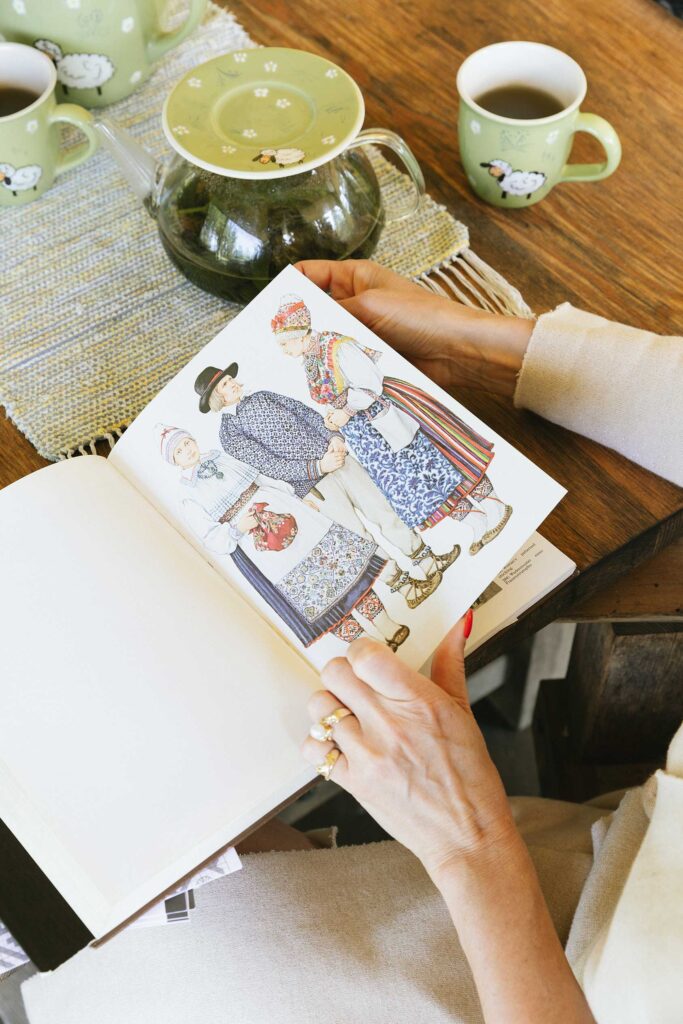

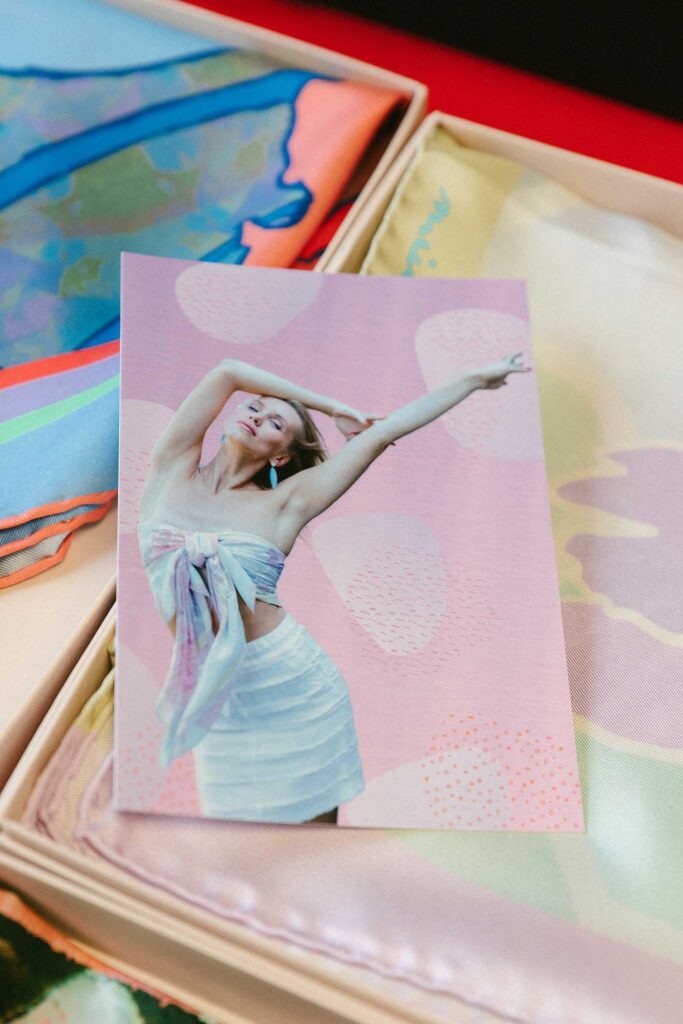

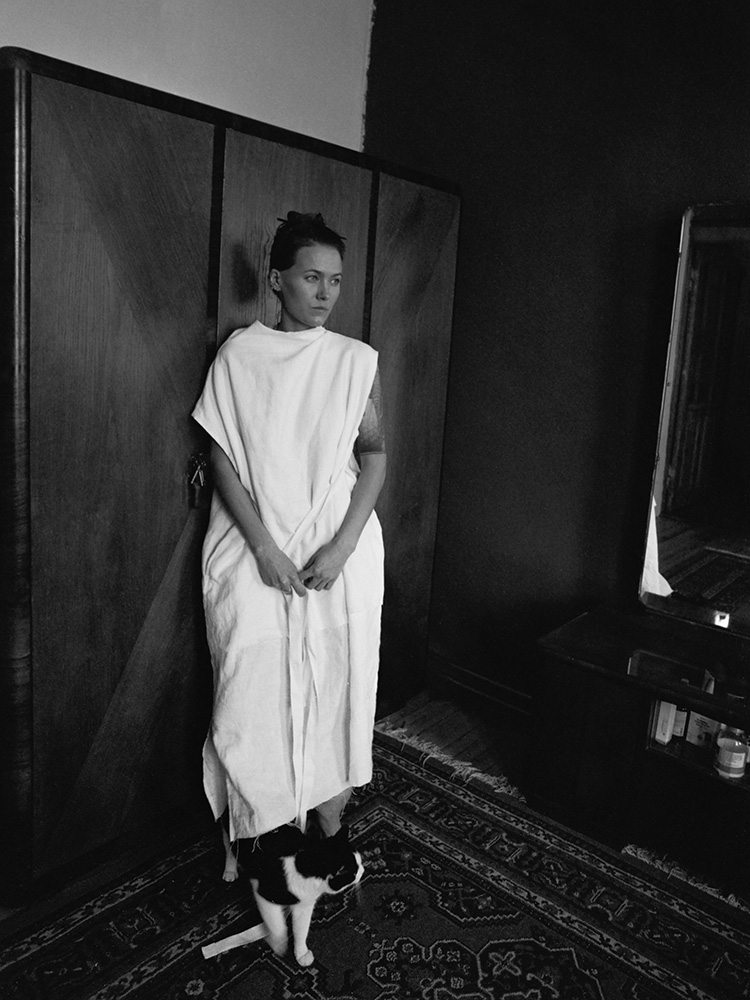

Tuuliki sees clothing as a form of playfulness and self-expression, a way of finding oneself. “It’s a potential open to everyone. To adopt a certain attitude and live it out. One day you’re one thing, the next day another, and clothes allow you to identify with different characters. For me, what matters most is inner alignment — that you’re the same on the inside and the outside, that there’s no contradiction.”

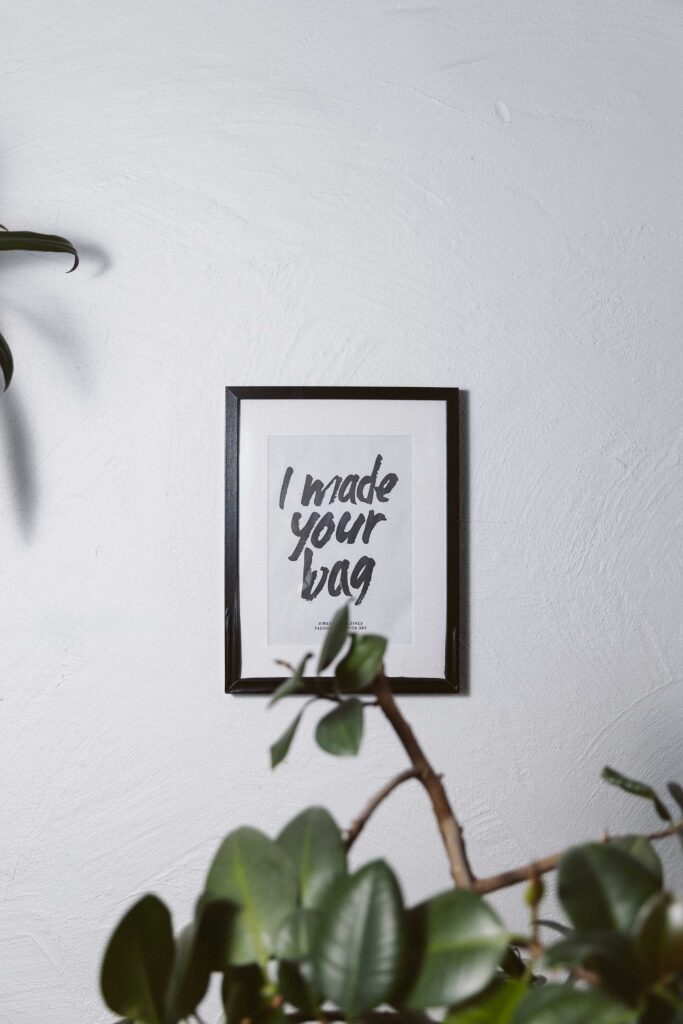

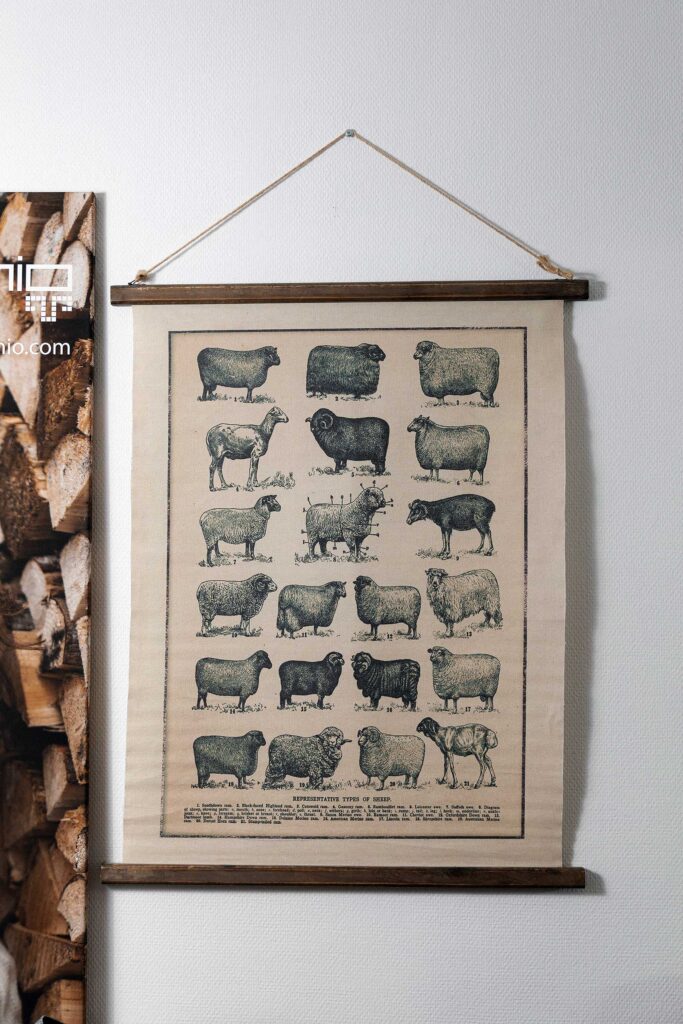

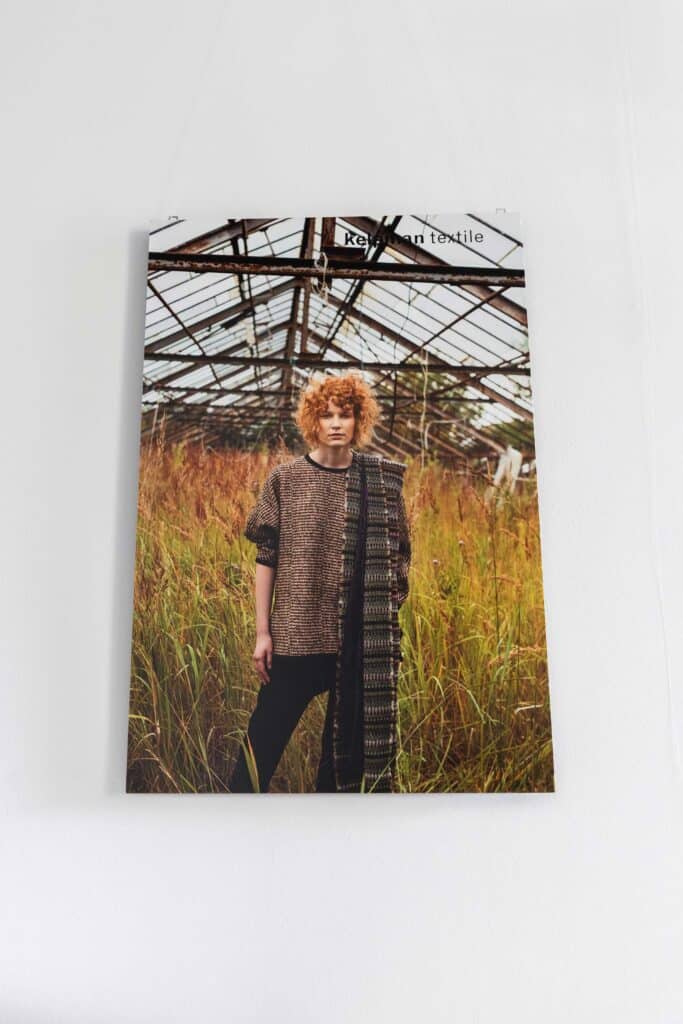

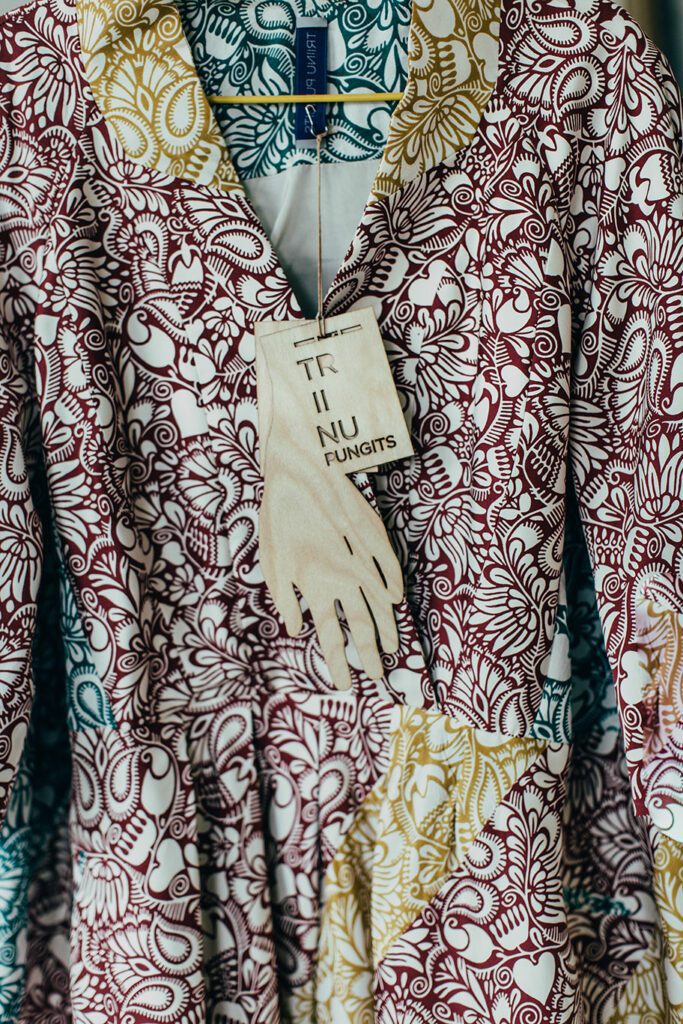

Tuuliki also highlights the more painful side of design — consumption and overproduction. “When I see those piles in shopping malls… it’s hard for me to breathe. And I think, oh no, I’m contributing to all of this as well. It really troubles me, and I’ve often thought that I don’t want to be involved in this at all.” That is precisely why she creates only from upcycled materials. “It allows me to work without guilt. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to function as a designer.”

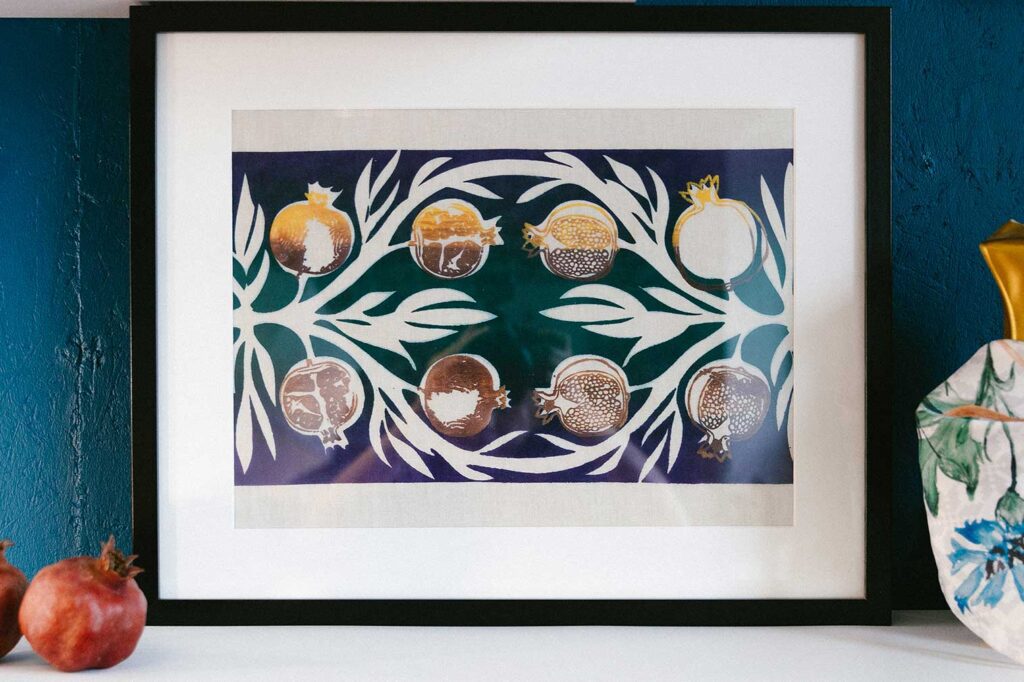

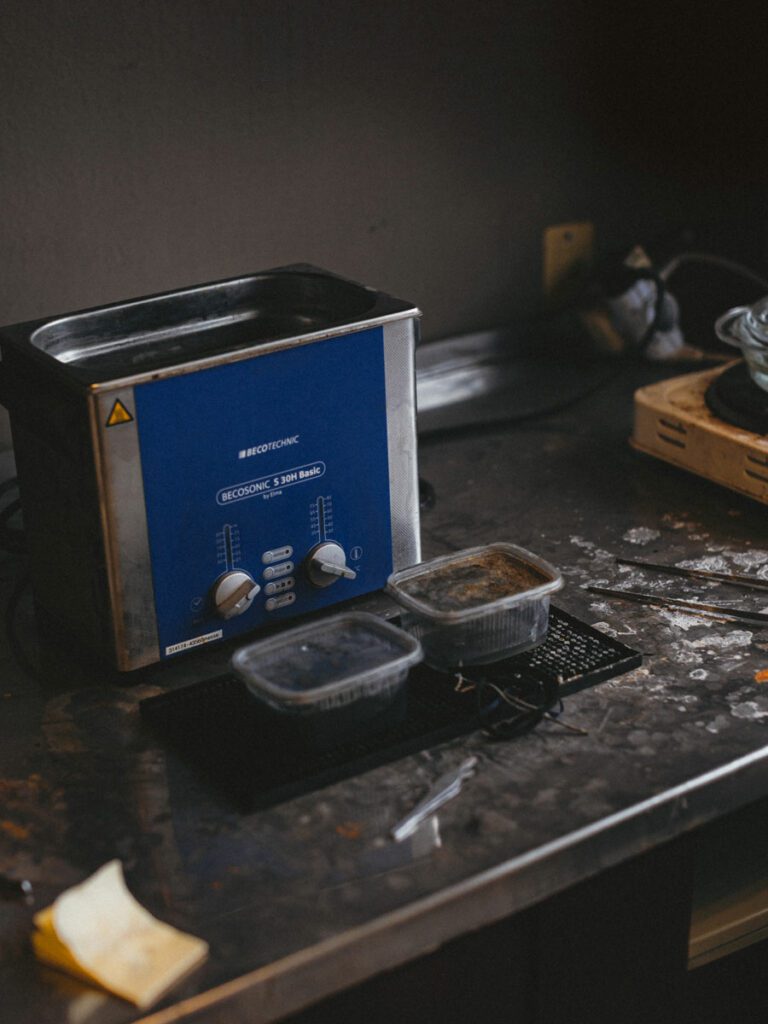

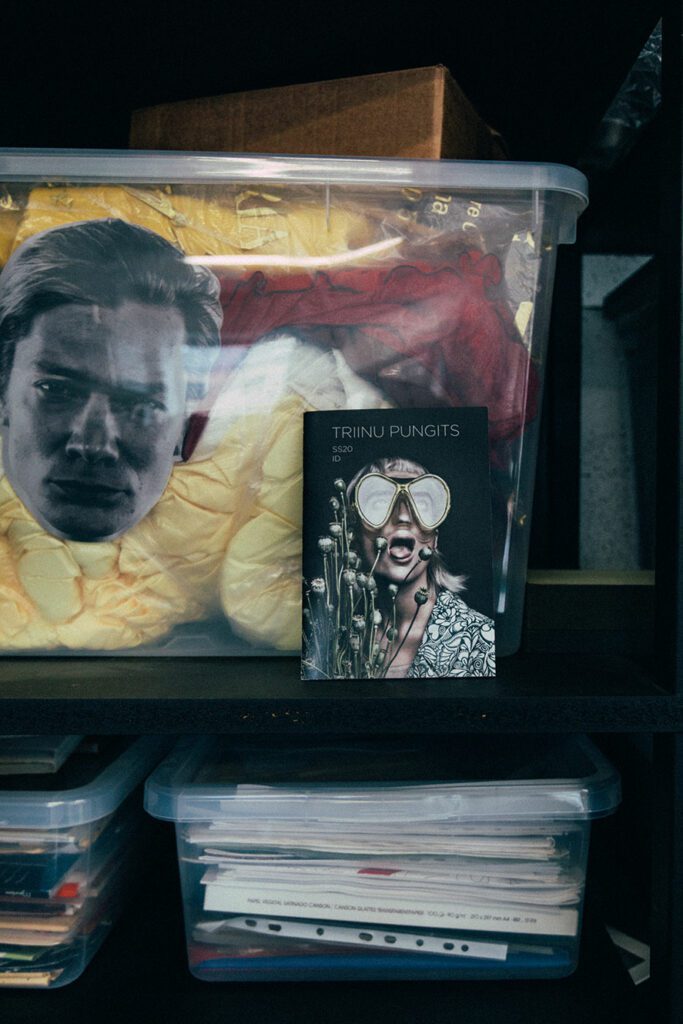

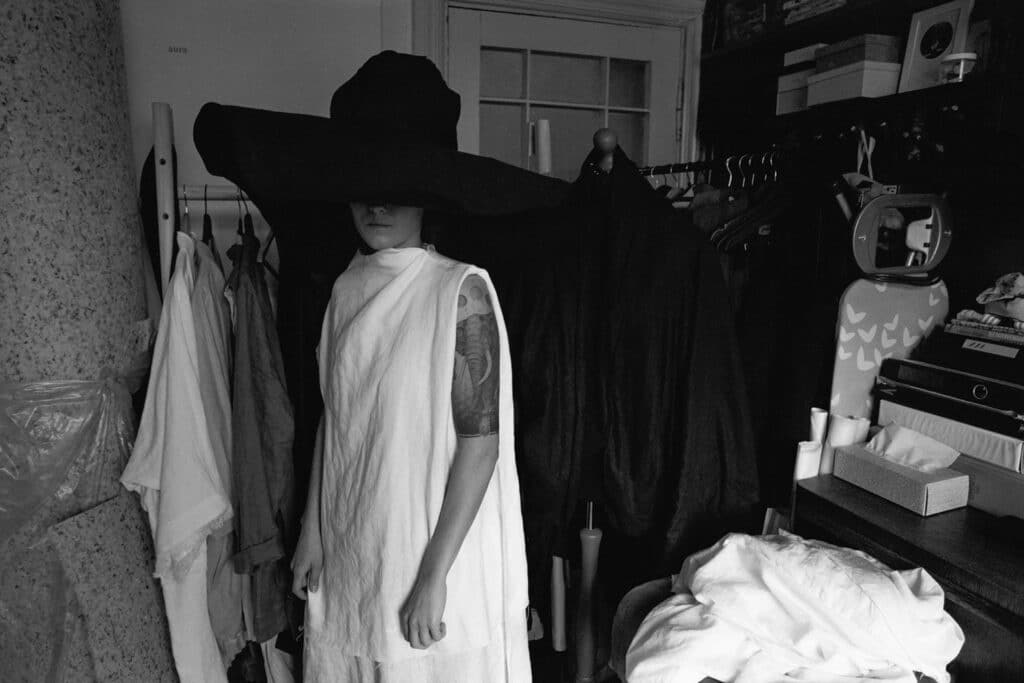

The name New Life Studio encapsulates the brand’s core philosophy. “It’s about giving new life to something that has become worthless to someone else and been abandoned,” Eva Lotta says. “We find new value in it and give it a new life.”

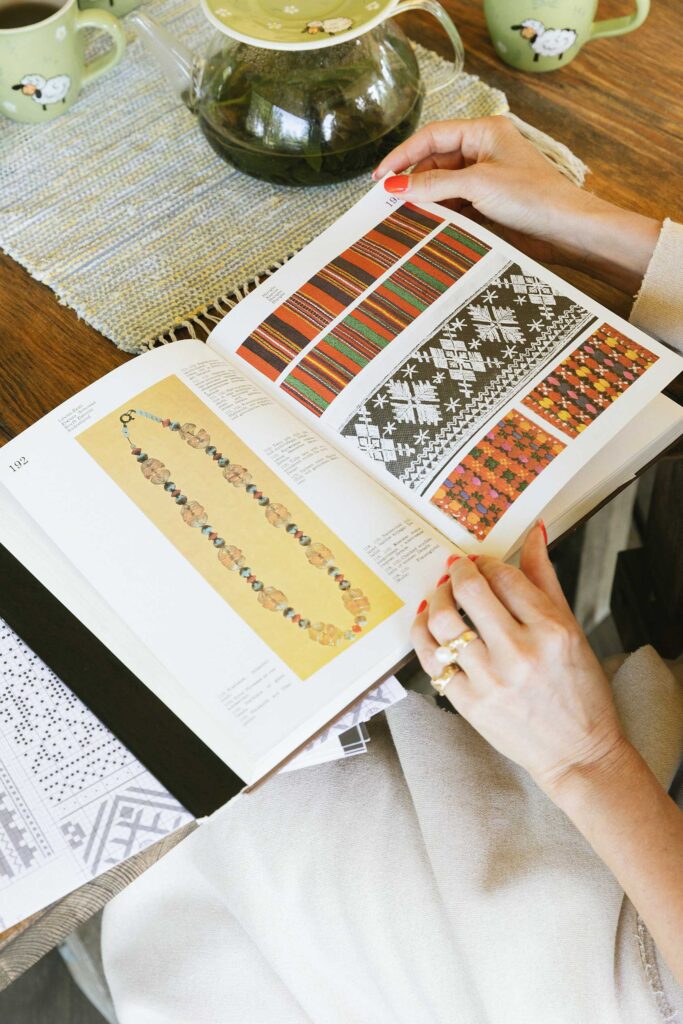

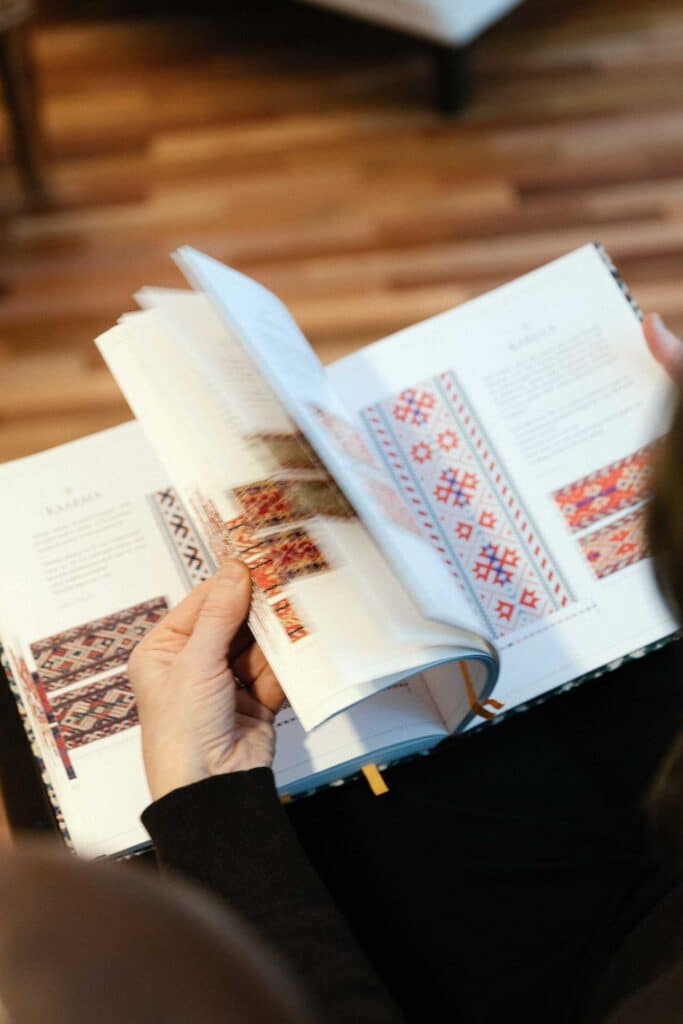

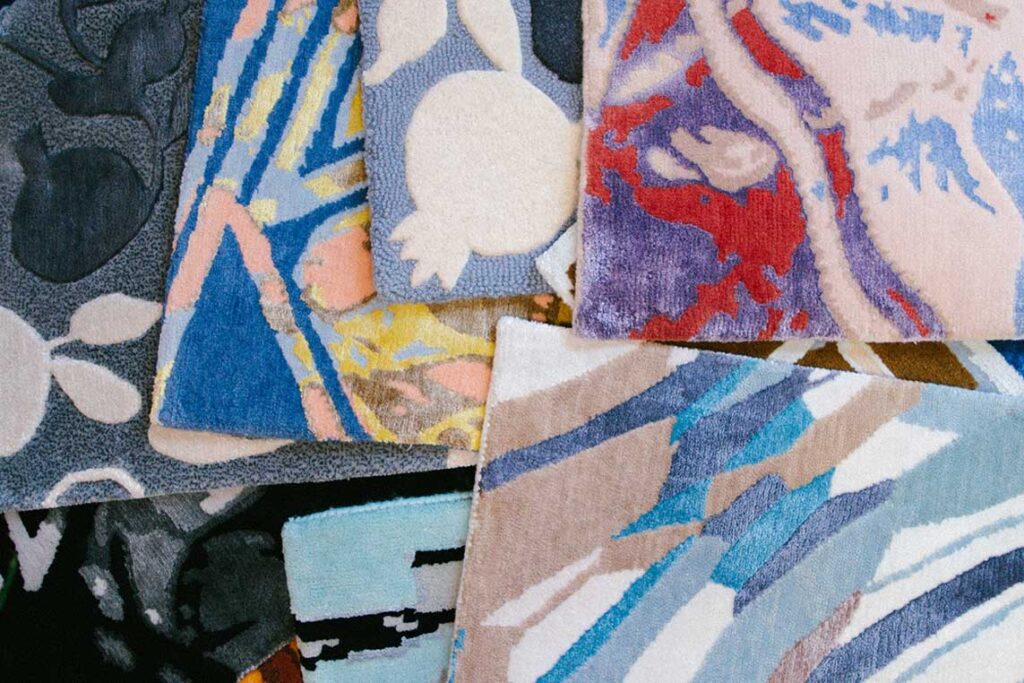

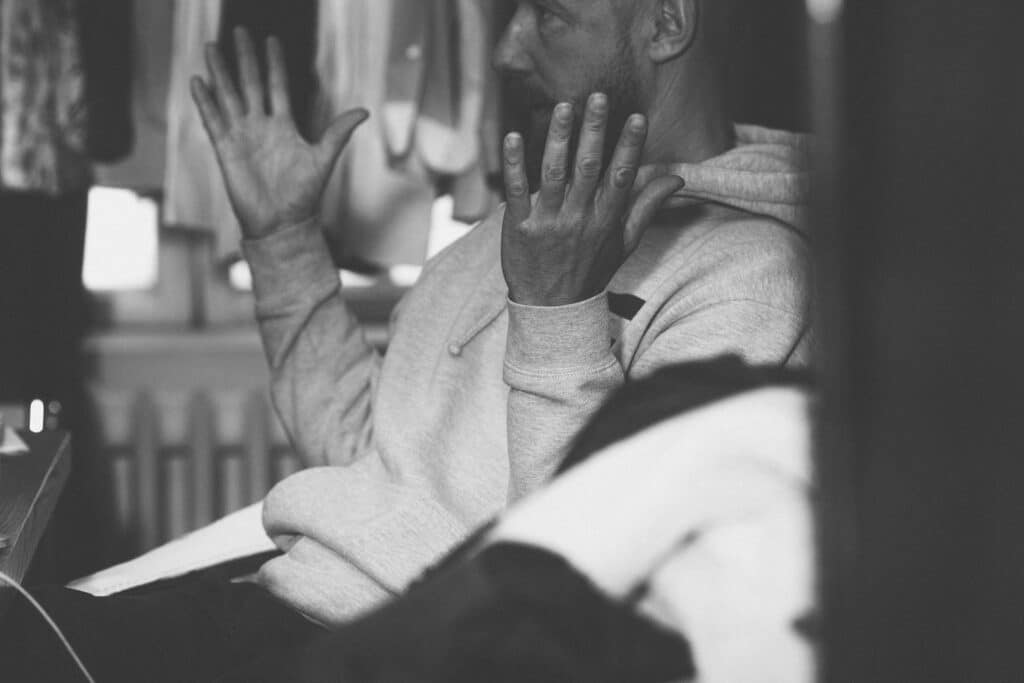

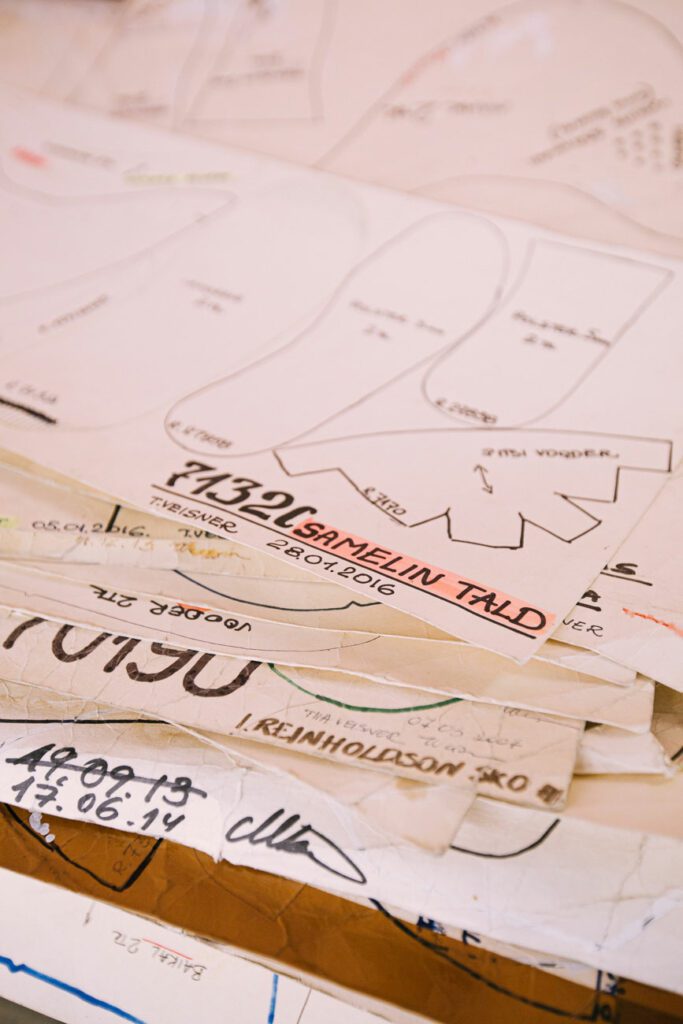

Although they operate under a shared name, each designer has her own distinct signature. According to Tuuliki, material is always at the center of her creative process. “Because I work with upcycling, my signature is very material-driven,” she explains. When she notices an interesting fabric in a second-hand shop, the idea immediately starts to take shape.

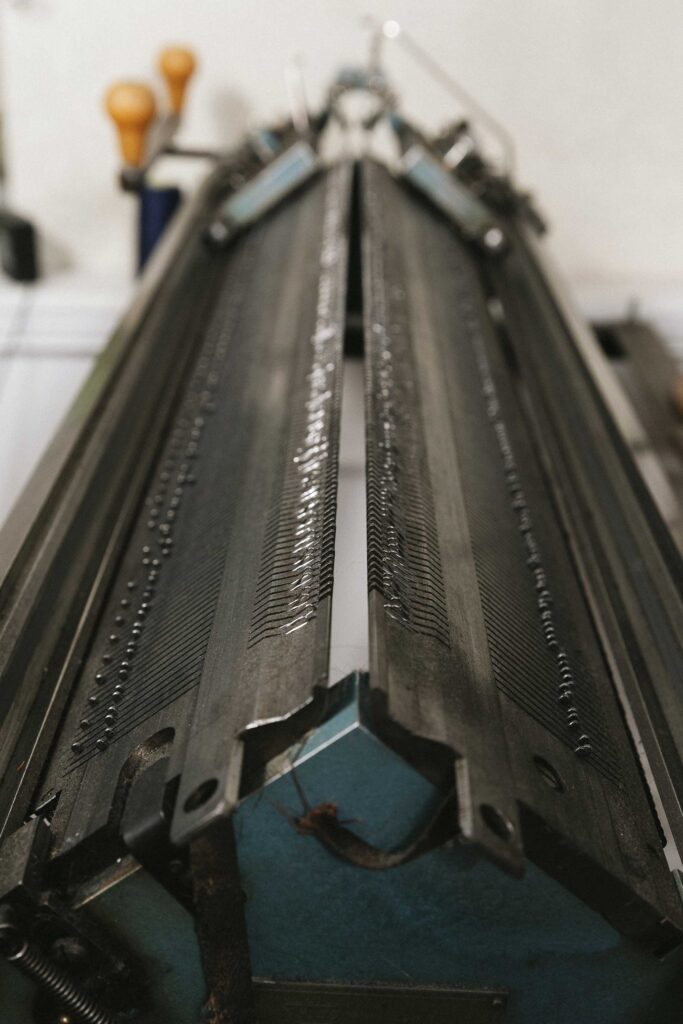

Since upcycled fabrics often come in small pieces, this inevitably shapes the final result as well. “Many items are made from ten different pieces simply because there aren’t three meters of the same fabric available. That’s the reason these pieces are the way they are,” Tuuliki says.

Eva Lotta’s design process, however, is often the opposite — she begins with a clear vision of the final outcome, which then guides the choice of materials. “That makes the process more complicated, especially with custom orders,” she says. “If a client has a very specific wish regarding material or color, it can be extremely difficult to find it second-hand.”

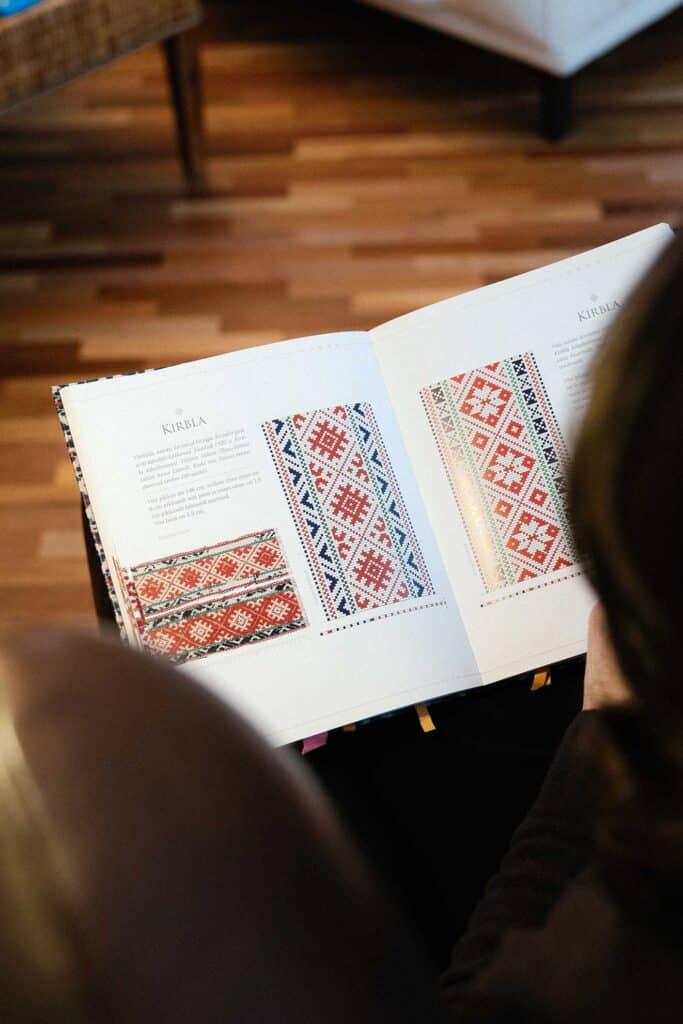

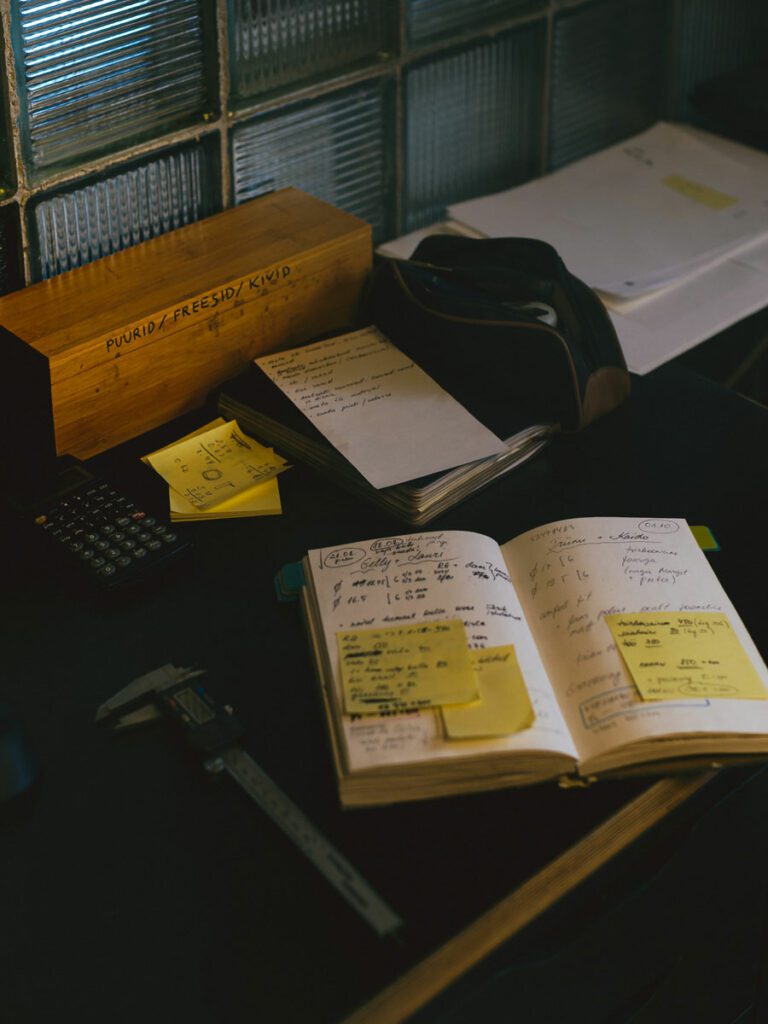

For both designers, sourcing materials is an integral part of the creative process. Tuuliki regularly visits reuse and second-hand centers, where she finds not only clothing but also curtains, tablecloths, and other large pieces of fabric. “Not everything has to be made from old garments — you can find a lot of unused fabric through reuse as well,” she says. Sometimes the search becomes almost like detective work: “If you need to finish a piece and are missing a section of a yellow sweater, you end up visiting ten different shops.” Most of the time, however, they find what they need in their own material stock. “It depends on the project — whether we’re creating for ourselves or working on a commission,” Eva Lotta adds.

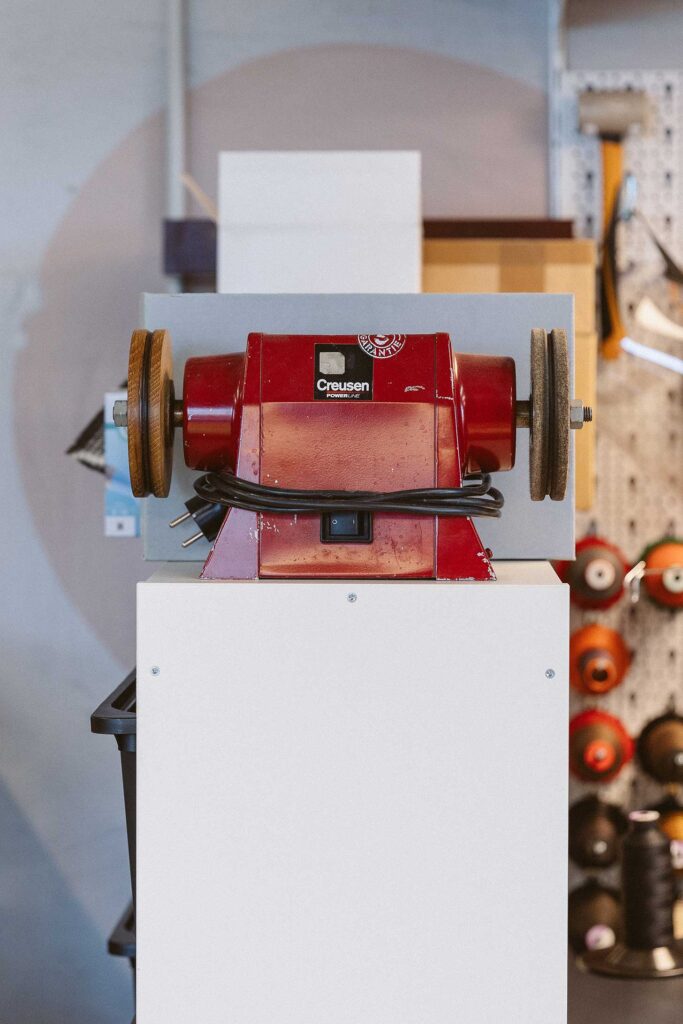

For Eva Lotta, the most meaningful designs are those created using the unravelling technique she has developed herself. “I use knitted garments from thrift stores that are often among the very last items left on five-cent days — pilled and seemingly unwanted by anyone,” she explains. Through unravelling and reworking, an entirely new texture and material emerges.

Eva Lotta and Tuuliki’s collaboration extends beyond design alone — New Life Studio has also evolved into a community space. “For the third year already, we’ve been running creative sewing workshops. People come to us with half-finished projects they have at home. Maybe something needs to be taken in, repaired, or completely transformed. We provide the machines and guidance, and everyone can come with their own project,” Tuuliki explains. At the same time, she emphasizes that this is not a typical course where everyone learns the same thing. “Some want to make a new piece, others want to rework an old one — we guide everyone individually.”

Speaking about the future, Eva Lotta is candid: “My goal is quite simple — that I can continue as a designer. That it would truly be possible. All of my energy goes into that.”

Tuuliki adds that above all, she hopes the studio will start hosting the kinds of events and gatherings it was created for. “That the shop area would open, that people would come in from the street, that there would be movement and creative life.”

“And a bit of stability would be nice too. I don’t know if that’s even possible, but I hope so,” Eva Lotta adds.